Chess is perhaps the most widely known board game in the English-speaking world. If you’re reading this blog, you’re probably familiar with it, whether you played it as a kid, joined a Chess club, or collect original Nathaniel Cook sets.

But I am not going to assume that everyone is familiar with it. You might have lived a sheltered life, or been one of those kids who “played sports” and “had friends.” If this is the case, and you are repentant for your ignorance of the Immortal Game, you’ve come to the right place.

Pieces

A Chess set consists of an 8x8 checkered square board and a total of 32 individual Chess pieces. Each player has the same pieces -- eight pawns, two rooks, two knights, two bishops, one queen, and one king -- but they are different colors, conventionally called "black" and "white" regardless of the actual colors used.

A pawn is the smallest piece, usually a short little thing with a ball on the top. Rooks are also short, and look like kind of like towers or turrets. Or…cylinders. Knights are horsies. Bishops are like the pawn’s older brother, but with a slice cut out of their heads for some reason. Kings are the tallest piece and have crosses on their heads, and queens are the second-tallest, topped with some kind of crown-ish sort of thing.

Got it? Okay, good. That’s all you need to know. (That is not all you need to know. And there will be pictures later, so that description was pretty much unnecessary. Carry on)

If you don’t have a chess set but would still like to play, point your internet machines here, where you can find a downloadable board and complete set of pieces. Assembly instructions for the pieces are on that page as well.

Setup

The board is positioned between both players, and should be rotated so that each player has a white square in right-hand corner closest to them.

The pieces are a little tricky looking at first, but it’s simpler than you might think. The rows closest to each player has rooks in both corners, knights next to them, then the bishops, then the king and queen. The queen is always positioned on the color of the player, so the white queen should always start on a white space, and vice-versa. The next row up is filled with pawns.

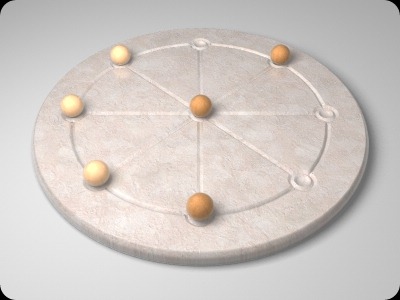

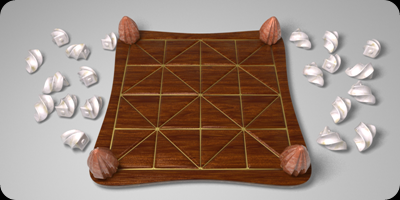

The setup of a Chess game. From left to right on the nearest row the pieces are rook, knight, bishop, queen, king, bishop, knight, rook.

The setup of a Chess game. From left to right on the nearest row the pieces are rook, knight, bishop, queen, king, bishop, knight, rook.

Play

Players alternate moving their pieces, one at a time, in pursuit of checkmate (explained below; could be very crudely summed up as “killing the king”). White moves first. Always. Letting black move first is a class C misdemeanor in the United States (it’s an older rule).

Pieces can capture their opponent's pieces by moving into their space. When a piece is captured it is removed from the game, and the piece capturing it assumes its previous position (with one exception, en passant, explained below).

Each piece moves differently. Understanding the movement of the pieces is probably the most important thing to know, so here goes:

Pawn

Although it is perhaps the most basic piece, the pawn has the most complex movement. It can move one square forward (relative to the player who controls it), unless it has never moved before, in which case it can move two spaces forward (when moving two spaces, you can’t “jump” over another piece -- the way must be clear).

Unlike every other piece in the game, it doesn't capture like it moves. It can only capture diagonally forward, as shown. It still moves to occupy the space.

Rook

The rook has the simplest movement of any piece. It can move as far as you choose in any orthogonal direction, and captures the same way.

Like all pieces with "long" movement (the rook, bishop, and queen), the rook can't jump over or move through another piece, be it friendly or not. When capturing, the rook moves to occupy the opponent's space and must come to a stop there.

Bishop

Bishop is like the anti-rook: it can only move diagonally. Each player has two bishops, one that can only traverse white squares and one that can only traverse black squares.

Queen

The queen is the most powerful piece. It can move as far as you choose in any direction, orthogonal or diagonal. Like a rook and a bishop got it on. Or maybe the rook and the bishop are like the dizygotic twin children of the queen, each one having absorbed a different power from their estranged mother.

King

The king is like a much, much weaker queen, with a less complicated family history. It can move in any direction, but can only move one space (maybe the offspring of a queen and a pawn? Anyone?).

Knight

The knight is a little tricky. Think of it as moving two squares forward and one to the side, so two squares up and one square to the right, or two squares to the left and one square down, etc. It essentially moves in an "L" shape.

The knight is unique in that it is the only piece that can "jump" over pieces. While other pieces can't move past an obstruction, knights can jump over both friendly and enemy pieces (definitely adopted, if you ask me).

Capturing

Pieces can capture their opponent's pieces by moving onto the square they occupy. When this happens, the captured piece is removed from play.

Kings cannot be captured, only checkmated (explained…right now!).

Check and Checkmate

When a player is "attacking" his opponent's king -- that is, if you move a piece in such a way that it could take the king on your next turn -- then your opponent is "in check." It is customary to say “check” when you check your opponent to alert him to the fact.

If a player is in check, he must get out of check instantly (on that turn), either by moving his king to a safe square, taking the piece that has put him in check, or moving a piece between the king and the attacker (the last not applying if he is being checked by a knight).

If there is no legal move that will get the king out of check, it's called Checkmate and the player who effected it wins the game. It’s customary to say “checkmate” if you manage this. It is then customary for the loser to flip the board and run off crying.

An example of checkmate: white is being checked by the rook and has no way to get out of it. He can't take the rook, as it's being guarded by the bishop; he can't move to the side, because of the knight; and he can't move diagonally forward, as that would put him back in check from the rook. Oh, the checkmanatee!

An example of checkmate: white is being checked by the rook and has no way to get out of it. He can't take the rook, as it's being guarded by the bishop; he can't move to the side, because of the knight; and he can't move diagonally forward, as that would put him back in check from the rook. Oh, the checkmanatee!

It is against the rules to put your own king into check. You cannot move your king into check, and if there is a piece blocking your king from check, you cannot move that piece in such a way that it exposes your king to danger.

Confusing Things

While everything listed above should be enough for a simple game between friends, the rules of Chess don't stop there. There are a few more that you should be aware of.

Note that only the first two listed here are actually that important. You probably won't have to worry about the rest for a while. Or maybe you will. Better bookmark the page for future reference just in case. And tell all your friends about it. Maybe get the logo tattooed on your chest. Set it as your home page. You know, whatever.

Castling

Castling is a special move that players can do once per game. It basically consists of the king and a rook breaking all the other rules of Chess, and it can be extremely useful. However, it can only be performed if all of the following conditions are met:

- The king is not in check.

- Neither the king nor the rook have moved.

- There are no pieces between the king and the rook.

- There is no space between the king and rook that is "under attack" by an enemy piece.

Okay, so here's what happens: the king slides two spaces over towards the rook, and the rook jumps over to the other side of the king.

For a king-side castle (castling with the rook nearest to the king), the king will be next to the rook, and the rook will just jump to the other side. For a queen-side castle, castling with the other rook, there will be a space between the king and rook, and the rook will have to move further to get to the other side of the king. He can handle it, though. Don’t worry.

An example of a legal king-side castle

An example of a legal king-side castle

Castling takes up a turn just like any other move.

Furthermore, although this will probably never come up, you cannot castle with a promoted pawn. Even if the pawn has just become a rook and the rook has not moved, and the king is not in check, and everything else holds true, this is against the rules (this sounds obvious, but it wasn't an official rule until 1972, when someone spotted this loophole).

Promotion

If a pawn is able to cross the entire board and land on the furthest row from the player who controls it, it can be promoted to any other piece (besides king) of the player's choosing.

Almost everyone picks a queen, and it's usually the best choice, but very occasionally an extra knight can be more useful. You are technically allowed to pick a rook or bishop, but there's absolutely no reason to -- the queen is completely superior to both.

En Passant

So in case pawn movement wasn't confusing enough already, just wait: they have another oddity.

If a pawn is positioned in such a way that it is two squares away from the opponent's pawn line, and your opponent moves a pawn two squares forward, so that it is now next to your pawn, you can take it by moving your pawn diagonally forward so that it is behind your opponent's pawn, which is then captured.

Wait, what? Think of it like this: even though your opponent moved his pawn two spaces forward, you can capture it like it had only moved one space forward, provided you have a pawn handy.

If black moves his pawn forward two spaces, white can capture it with his pawn as shown.

If black moves his pawn forward two spaces, white can capture it with his pawn as shown.

This must be done on the turn immediately following your opponent's movement of his pawn. If you don't take it immediately, you forfeit your right to use en passant. Also, only pawns can do this -- you can’t use en passant with a bishop and expect to get away with it. Not in my house.

So, why on earth does Chess have such a bizarre rule? Well, back in the day, pawns couldn't move two spaces forward on their first move. They had to move one. But when the two-space movement rule became popular, which allowed games to get started faster, people realized that pawns could slip by other pawns by moving two spaces ahead, and they didn't like this (caused some icky promotion issues or something). So they came up with en passant, which is French for "in passing." The basic rationale is that the pawn isn't "jumping" forward by two spaces, it's moving forward one space, and then moving forward one space again. So it's like a two-step movement process. Thus the pawn that is performing the capture is capturing it when it's only "half done" with the full movement.

Draws

At the beginning of a turn, if things aren't going very well, a player can offer a draw to his opponent. If his opponent accepts, the game ends in a tie. If not, play continues as usual, with one player a little more bitter than before.

Now, you don't offer a draw because you're about to lose and would rather tie -- that's really not the point of it. Draws are rather agreed to if neither side has a clear path towards victory. For example, if no one has enough pieces to force an effective checkmate, they may choose to draw the game rather than continue playing.

There are some other circumstances that can force a draw without the other player necessarily consenting, as discussed below.

Resigning

If a player's defeat is imminent, he can choose to resign, traditionally by knocking over his king. This results in a victory for the other player, of course.

Stalemate

If a player isn't in check but doesn't have any legal moves -- that is, any possible move would put the player into check -- this is called a stalemate, and results in a draw.

An example of stalemate for Black. Neither pawn can move, and any move the king would make would put him in check.

An example of stalemate for Black. Neither pawn can move, and any move the king would make would put him in check.

Stalemate generally occurs near the end of the game, and should be avoided by a skilled player. In the above example, white would have been wise to avoid stalemate -- he could have won, but will instead have to accept a draw.

Fifty-Move Rule

If no pawn has been moved and no piece has been captured in the last fifty moves, the game can be declared a draw. You probably won't have to worry about this -- ever -- but it is a rule that players recognize in tournament games. By the time you get to that level, however, you should probably not be relying on this site for your Chess info (note: ignore that. Don’t forget me when you’re famous).

Three-Fold Repetition

If the same position is repeated for three turns, one of the players can declare a draw, although this is not required.

For example, if a rook moves to check a king, and the king moves away, and the rook moves to check him again, and the king moves back, and the rook moves back, etc.

Tournament Rules

This article leaves a few things out of the rules. For example, the use of clocks and different timing rules, notation, touch-move, Chess terminology, etc. These aren't things you have to know to play with a friend, but they are important if you ever move into tournament play. Maybe a future article can address that.

Strategy

More has been said on the topic of Chess strategy than perhaps any other board game (note: I made no attempt to even almost confirm that statement. In fact, now that I think about it, that honor probably goes to Go, simply because it's been around so much longer. Whatever. Disregard that). The second book ever printed in the English language, after the Bible, was The Game and Playe of Chess, by William Caxton. Chess is an Olympic sport (although so are Korfball, Orienteering, and Lifesaving. Like, saving lives. Is a sport.).

Anyway, like I was saying, Chess strategy is a big deal. I can't even breach that thin, nasty film thing that develops when you leave the strategy sitting out too long, but I can offer a few general pointers for the absolute beginner:

- Most importantly, develop your pieces as soon as you can. This means that you should bring a lot of pieces towards the center of the board, rather than just bringing out a few and moving them around a lot. More pieces out on the board means more options, more guarded pieces, etc.

- It’s a good idea to start by moving your king’s pawn forward two spaces. This opens things up for your queen and a bishop, and will let you castle in only a few moves, giving you a head start on the rooking. Queen’s pawn forward is also good, if you prefer.

- Don't bring out the queen too early. Overvaluing the queen is a very common beginner's mistake -- it’s easy to spend the whole beginning of the game running your queen around trying not to get it killed while your opponent develops all of his pieces. In general, it's better to bring your knights out first, then bishops, then finally queen and rooks -- while not neglecting your pawns! It’s like my mother always said, “no queens until you’ve finished your pawns.” She never said that. Segway...

- Maintain a good pawn structure. You should try to make sure that all your pawns are being guarded by another pawn. Don't move pawns forward undefended; keep them in diagonal lines, so that each one is being guarding by the one behind it.

- Try to control the center of the board. There is a four-square hot-zone in the very center that you should, as a general rule, strive to control. Pieces in the center can reach more squares on the board, and thus are more strategically powerful.

- Always remember that the goal is to checkmate the king, not to take pieces. Although early on capturing pieces and gaining territory will be your main goals, always be on the lookout for opportunities to move towards mate once a few pieces are out of the way. Novices often focus more on getting the opponent's queen than king, which is simply naïve strategy.

Although Black might appear to be losing, look again: he is one turn away from victory. The white knight takes his queen (this is the only legal move) and black moves his bishop in for checkmate.

Although Black might appear to be losing, look again: he is one turn away from victory. The white knight takes his queen (this is the only legal move) and black moves his bishop in for checkmate.

The only available choices are 8 and 3 + 5

The only available choices are 8 and 3 + 5

Victory for white. Wow, this game is really, really simple

Victory for white. Wow, this game is really, really simple

The setup of a Chess game. From left to right on the nearest row the pieces are rook, knight, bishop, queen, king, bishop, knight, rook.

The setup of a Chess game. From left to right on the nearest row the pieces are rook, knight, bishop, queen, king, bishop, knight, rook.

An example of checkmate: white is being checked by the rook and has no way to get out of it. He can't take the rook, as it's being guarded by the bishop; he can't move to the side, because of the knight; and he can't move diagonally forward, as that would put him back in check from the rook. Oh, the checkmanatee!

An example of checkmate: white is being checked by the rook and has no way to get out of it. He can't take the rook, as it's being guarded by the bishop; he can't move to the side, because of the knight; and he can't move diagonally forward, as that would put him back in check from the rook. Oh, the checkmanatee! An example of a legal king-side castle

An example of a legal king-side castle If black moves his pawn forward two spaces, white can capture it with his pawn as shown.

If black moves his pawn forward two spaces, white can capture it with his pawn as shown. An example of stalemate for Black. Neither pawn can move, and any move the king would make would put him in check.

An example of stalemate for Black. Neither pawn can move, and any move the king would make would put him in check. Although Black might appear to be losing, look again: he is one turn away from victory. The white knight takes his queen (this is the only legal move) and black moves his bishop in for checkmate.

Although Black might appear to be losing, look again: he is one turn away from victory. The white knight takes his queen (this is the only legal move) and black moves his bishop in for checkmate.