This is a very cool game invented by the mathematician Piet Hein in 1942, and then independently re-invented five or six years later by John Nash (the protagonist of A Beautiful Mind, if you’ve seen it). I’m not entirely sure, but I believe it was even referenced in the movie. Hein originally called the game Con-Tac-Tix, and it was known around Princeton as Nash, but when Parker Brothers decided to create a commercial version they called it Hex, which ultimately stuck. (It was also called Polygon at one point by less successful Danish marketers.)

Anyway, it’s a very interesting game that involves forming a connected line across a rhomboidal game board divided into a hexgrid. Sounds kind of mathy, right? It’s actually a really simple, fun game, and is the ancestor of many connection games to come, so it’s good to know how to play. It’s also really fun, so that’s a plus.

Equipment

The pieces for this game are a tad tricky. You need a lot. Up to 121 for an 11 x 11 board (the smallest ever really used), in fact. You probably won’t need anywhere near that many -- that’s the absolute maximum -- but you’ll still need a few. On average maybe about 20 to 25 tokens per player, which is certainly do-able. If you have Go stones those are absolutely perfect, although I realize most of us don’t.

The board used varies in size, typically from 11 x 11 to 19 x 19 (a nod to Go). Some boards use the intersections of a triangular grid, but the board I’m providing uses an actual hexgrid (although, to make it more friendly to a wider audience, I’ve chosen to go with a circular map -- if you have any objections, let me know via Twitter or Scribd). Grab it here, print it out, and enjoy -- but note that, due to the small size of paper, my usual advice of pennies and nickels won’t work. Anything small will, though -- beads, rocks, beans, backgammon pieces, bits of wood -- get creative and make it happen.

Since no token is ever removed from the board once placed, you can just fill in circles using two colored pencils, or with Xs and Os, or whatever. However, you’d end up eating quite a bit of paper before too long. To help remedy this, I’ve created some mini Hex boards, specially designed to be printed and colored on. Print them out and enjoy!

Rules

The goal of the game is incredibly simple: each player is trying to form a completely connected line from one edge of the board to the other by placing stones in any open space (the board starts completely empty). Each player is assigned a different pair of opposite edges that they must connect, so their lines must ultimately clash somewhere in the middle of the board, which is where the game really get’s interesting.

Formally put, players alternate placing tokens anywhere on the board. Each player places distinct tokens. The first player to form an unbroken line of their own tokens from one designated edge of the board to the opposite edge is the winner (you can’t win by connecting your opponent’s edges).

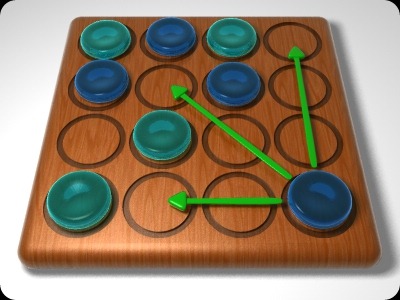

Victory for green. Those bowls haven’t changed in the slightest

Victory for green. Those bowls haven’t changed in the slightest

over the course of these images. Don’t tell anyone.

Simple, right? Yes, it is -- even with the following rule:

The Pie Rule

Like just about all connection games, and many games in general, the player who goes first has a pretty strong advantage. This is no good, so a very simple rule was devised (I don’t know by whom) to minimize this advantage. It’s called the Pie Rule, or sometimes the Swap Rule, and it works something like this:

Players decide randomly who goes first. That player places a stone on the board wherever he’d like. The other player then has a choice: he can either play one of his stones and start the game normally, or he can choose to switch colors with his opponent. If he did this, the player who placed the initial stone would then place another stone of the other color, and the game would continue normally from there. So, if the Pie Rule were invoked, the first player would play two stones in a row of opposite colors, and he would play from then on with the color of the second stone.

This way, if the first move is really good, the other player can choose to switch colors, so as not to be at a disadvantage. Of course, now he’s actually at an advantage, so the person going first will generally not play a very “good” first move, to minimize damage in case the colors switch.

Make sense? If not, here’s one of those lame examples using fake names that no one likes:

Mohammed and Barnaby are playing Hex. Before the game starts, Barnaby decides to play and white and Mohammed decides to play black. Barnaby is randomly chosen to go first, and plays a white stone on the board. Mohammed decides that it was a good position, so he invokes the swap rule. Now Mohammed is playing white and Barnaby black. Mohammed doesn’t place another stone -- Barnaby’s first move has become his. Instead, Barnaby places a black stone on the board and the game continues normally.

The Pie Rule is a great way to even out the game -- otherwise the first player would have a pretty hefty advantage, which is no good. But you may be wondering -- why is it called the Pie Rule? Why don’t people just use “Swap Rule” instead?

Well, the name actually comes from the cutting of pie. For real. It’s the classic fairism wherein one person cuts a slice of pie in half to share with someone else. The other person then chooses the slice that he wants. Since it can be safely assumed that the other person wants to get as much pie as possible, the first person wants to make the two halves as equal as possible so as not to be stuck with a small piece.

And that’s really all there is to it. Hex is a great game that anyone can get into, so consider yourself lucky that you’ve found it.

Hex was chosen as Tabletop’s first ever Game of the Month in June 2009. Congratulations, Hex! There’s no prize, obviously, but perhaps the increased attention will help you achieve the popularity you greatly deserve!

As shown. Like I said.

As shown. Like I said. The blue piece in the corner can only move to those three spaces; it cannot stop moving until it collides with something. Note that if it chooses the diagonal path, blue will lose the game, as that is a cornering move

The blue piece in the corner can only move to those three spaces; it cannot stop moving until it collides with something. Note that if it chooses the diagonal path, blue will lose the game, as that is a cornering move Blue demonstrating one of the many winning positions

Blue demonstrating one of the many winning positions

The game setup. Look at how cute those snails are. I spoil you.

The game setup. Look at how cute those snails are. I spoil you. White has won: it is black’s turn, and he must make

White has won: it is black’s turn, and he must make

Here, the white piece demonstrates valid moves while

Here, the white piece demonstrates valid moves while  The game is over: white will win in a few turns no matter what black does.

The game is over: white will win in a few turns no matter what black does.

Victory for black

Victory for black

Victory for black

Victory for black The Scarne Trap

The Scarne Trap

A European board

A European board How do you even suck this badly? That’s just awful.

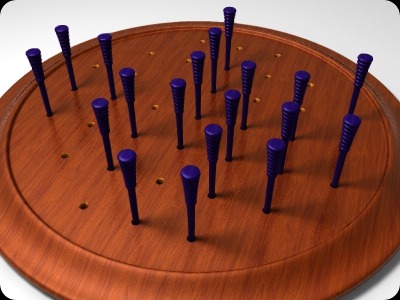

How do you even suck this badly? That’s just awful. There is no better way to score chicks than showing off your peg solitaire skills

There is no better way to score chicks than showing off your peg solitaire skills

The above example illustrated. The orange markers represent the unwise move.

The above example illustrated. The orange markers represent the unwise move. An example of stacking, if the white stack were to move onto the black stack

An example of stacking, if the white stack were to move onto the black stack

Rows of length 5, 4, 3, and 4

Rows of length 5, 4, 3, and 4