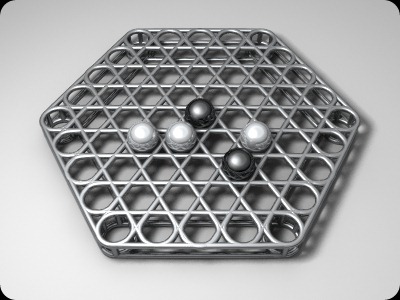

This is a neat little game that I discovered pretty much entirely by accident, but have grown to like for a novel but intuitively logical movement mechanic. It was designed in 2001 by Michael Shuck, and was one of the finalists of the 2001 8x8 Game Design competition (it lost to Breakthrough). That’s all I really know about it. So... onwards!

Equipment

The game can be played on a standard chess- or checkerboard with standard checkers or any stackable pieces. You'’ll need quite a few --29 for each player, to be precise -- so if your Checkers set can’t cut it you might have to consider coins. If you don’t have a board, print one here, as always.

Rules

The game is set up as shown, with a four-high stack in each player’s corner surrounded by two three-highs, then two lines of two-high stacks, and finally a line of single pieces (stacks of height one, for consistency). Different starting arrangements are of course possible -- you might consider nuking one of those lines of doublets if you’re low on pieces, for example, or just do something completely different. This is merely the setup suggested by the designer.

The goal of the game is simple: to capture your opponent’s king. By capture, though, I don’t mean remove (there are no “captures” in the traditional sense in this game), but rather “dominate” -- gain control of the stack by landing a piece on top of it (as in Focus). And by king I don’t mean a single piece, but rather a dynamically defined stack. More on that later. First: moving your pieces around.

Moving and Tumbling

There are two types of moves, standard “moves” and “tumbles.” I’ll talk about tumbles in just a second -- for now, moves:

At any time, you may move the top piece of a stack to a diathogonally adjacent space (assuming, of course, that your piece is on top). For stacks of only one piece, this would involve moving the entire “stack.”

You don’t have to move on to an empty space, though -- if there is another stack adjacent to you, you can move the top piece onto the other stack, regardless of any potential height difference. For example:

And that’s all there is to moves. Fairly simple -- short-range; covers a little ground. But what if you want to move a whole stack?

Enter the “tumble.” This is pretty much exactly what you might expect -- knocking over a stack and having the pieces tumble into new areas. It’s not as messy as that may sound, though -- essentially it means laying out the pieces of a single stack in a straight line such that the top of the stack lands furthest away. Alright, that’s confusing. Let’s do pictures.

As you can see, each piece in the stack moves, and once the tumble is complete the space that the stack used to occupy is completely empty (in other words, the bottom of the stack doesn’t stay where it was -- I could see this as being potentially confusing. I also smell a simple variation). You can tumble a stack in any direction including diagonals. If a piece tumbles onto another stack, the tumbling piece goes on top, as you might expect. So for example:

Oh, and one other thing -- if you tumble into an edge or corner, the edge “stops” the tumble, and all pieces remaining that still need to be tumbled are not tumbled. The is the only situation wherein a tumble can stop early -- normally it must continue until it’s been laid completely flat.

Kings

As I said before, the goal is to capture the enemy king. As I also said before, “capturing” just means getting one of your pieces on top, which can happen either by moving onto it or tumbling over it. But before we can do that, we must know: what is the king?

At any given time, a player’s king is the tallest stack made up entirely of his own color -- his tallest “pure” stack, if you will. But what if a player has multiple “highest” stacks? Well, then they are all kings. Sounds pretty good, right? Now your opponent has to capture all of them, right? Nope. If you have multiple kings, you lose if any one of them is captured, so it’s usually best to make sure you only have one king. Your king can change every time you make a move (if you make a new highest stack, if you tumble your current king, etc), so make sure you’re mindful of where your kings are!

reused this from the preview image. Shhh.

Obligatory closing comment: and that’s all there is to it!

Yes, I know that’s actually a trihexagonal tiling. I’m hoping you don’t.

Yes, I know that’s actually a trihexagonal tiling. I’m hoping you don’t. Now it makes sense, I hope. Black’s only response is a losing one.

Now it makes sense, I hope. Black’s only response is a losing one.