What a weird game. That’s all I can really say -- this is just a weird game. It’s incredibly simple and almost instantly familiar, but at the same time the gameplay is almost completely foreign. It’s weird.

Why is it so weird? Well, for starters, it was designed by a computer. I don’t know about you, but that throws up a couple weird flags for me. It is the only game I’ve ever heard of to have such an origin, and it’s interesting that such a unique and creative game came out of a program.

The “designer” in question is a program called Ludi which, as far as I’ve garnered from some light googling, takes in the rules to a few dozen games, mixes them up and scrambles things around, and then spits out a brand new game. As far as I can tell, Yavalath seems to be its flagship offering, but I’m sure there are many others out there that I just haven’t heard of yet.

Okay, so the game came from a program. But where did the program come from? It was created by none other than Cameron Browne, a rather big name in the realm of modern abstract strategy games. He has written what is still the only book on Hex strategy (Hex Strategy: Making the Right Connections, 2000) as well as a great compendium of many other connection games (Connection Games: Variations on a Theme, 2003). He also has no shortage of original games to his credit, many of which you will no doubt see here in the future. But enough of this -- on to the game!

Equipment

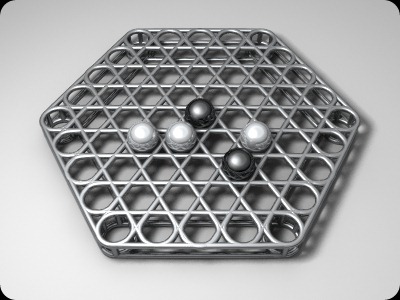

The game is played on a standard hexagonal hex board with five squares to a side. If you have an Abalone board lying around you can use that, or, if not, you can print one here and play with checkers or coins or whatever else.

The game can be played on a larger board as well, although it probably isn’t necessary unless playing a variation. Depending on how good you are, you could need anywhere from ten to thirty pieces each, so make sure you are well stocked.

Rules

The game couldn’t be simpler: players take turns dropping pieces anywhere on the board trying to make four in a row. If you make four in a row you win -- but if you make three in a row before then, you lose. It is this losing condition that makes the game so interesting, and from it the strategy arises: you don’t try to make four in a row. You try to make your opponent make three in a row.

How do you do this? Well, by forcing your opponent to block you from getting four in a row in such a way that he makes three in a row doing so. Make sense? Of course not. But just look at the picture.

Forcing moves like this are pretty much the backbone of the gameplay, which generally doesn’t last as long as other comparable games simply due to the fact that there are so many times where you don’t really have a choice about where you go -- you have to block or prevent a future three in a row, etc. Games generally play out quickly in exciting sequences of forced moves. It’s a fun game. Get on that.