Lines of Action is a weird one, both in play mechanics and victory condition. It’s a modestly popular game these days, as far as abstract strategy games go, but it’s not exactly the biggest game around. Which is a shame, because it really is unique and entertaining -- and odd combination of connection and movement that you won’t want to miss. It’s interesting in that there are so many ways of accomplishing the same simple goal -- but I must move on.

It was invented by Claude Soucie, but I’m not exactly sure when. I would guess some time in the sixties, as Sid Sackson included it in A Gamut of Games (1969), but it is possible that it’s even older than that (Claude Soucie was a contemporary and friend of Sackson -- when I get my copy of Gamut back I’ll check if there’s any note about the design date).

But enough of the boring bits -- to the game!

Equipment

Standard chessboard; twelve tokens per player. As always, you can find chessboards here and use whatever you have lying around as tokens.

Rules

In the standard game, the board is setup like this:

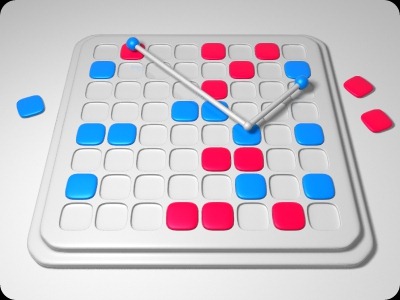

However, Soucie himself proposed an alternate setup, referred to as the Scrambled Eggs variant. It looks like this:

I assume that Scrambled Eggs takes longer to complete than standard Lines of Action, but I can’t swear to this.

Anyway, regardless of the setup, the game itself is the same: players alternate moving their pieces around the board in an attempt to join all of their tokens into a single contiguous body. What? Basically, you’re trying to get all of your tokens to touch (diathogonally). An example wherein blue has won:

It’s a simple enough goal, but accomplishing it is severely complicated by the movement mechanic...

Each turn, players must move one of their tokens in any direction (No passing). The number of spaces it moves must be equal to the number of tokens in that line of movement (the entire row or column or whatever along which the piece is moving). So the number of spaces you can move depends on the direction in which you’re moving -- a given piece may be able to move two spaces in one direction and one in another, or whatever.

There are a couple of other restrictions: you cannot jump over an enemy piece (although you can jump over a friendly piece), and you cannot move off the board (obviously). You can land on an enemy piece, however, in which case the piece you landed on is captured and removed from play. But be careful -- the fewer pieces your opponent has, the fewer he has to join together! Often it is disadvantageous to capture pieces, but sometimes it is useful -- breaking a key link in your opponent’s connection, for example.

Here’s an example of all the possible moves of a single piece. As you can see, there are only two. The first is to move four northwest (as there are four pieces total along that line of movement) and capture the red piece; the other is to move two spaces northeast. Note that the piece cannot move north or southwest because doing so would involve jumping over an enemy piece, and any other direction would either go off the board or land on a friendly piece, which is not allowed.

If a player makes a move that results in both his and his opponent’s pieces becoming joined at the same time (for example, if capturing an opponent’s only unconnected piece), the player who made the move is the winner. Also, if your forces are ever reduced to only one piece, you win automatically, as “all” of your pieces are connected.

And that’s it! Go forth and enjoy!