This is a simple game you’ve probably never heard of that, interestingly, was not originally conceived as a board game. It started life as a video game and was later adapted to the physical world -- the reverse of the usual process.

As you can probably guess from that, it’s a pretty recent game. It was invented in 1988 by Dave Crummack and Craig Gallery, who originally called the game Infection (which makes a lot of sense given the gameplay). In 1990 it was released in arcades under the name Ataxx, by which we know it now.

I played a variant of this game called Hexxagon quite a bit when I was a child -- it’s one of my earliest memories of video games. As such, I have a preference for the hexagonal board, but I will be describing the classic game here. If you’d like to play Hexxagon (it’s a better game, in my opinion), the rules are exactly the same, but the board is a hexagonal hexgrid (like Abalone) and each player starts with three pieces (positioned alternately in each corner).

Equipment

The game can be played on any size square grid board. For the sake of simplicity, I’ll be using a standard 8 x 8 chessboard, which you can print here if you’re lacking. Each player will need a large number of tokens as well -- easily up to forty and never more than sixty-four.

If you have Reversi pieces, use them! Not only will you need half the pieces (sixty-four, instead of sixty-four of each color), but pieces change just about every turn, so it will save you a bit of time (since you won’t have to swap out pieces each time).

(If you want to play Hexxagon, use an Abalone board. They are identical. If you don’t already have one, they can be found here.)

Rules

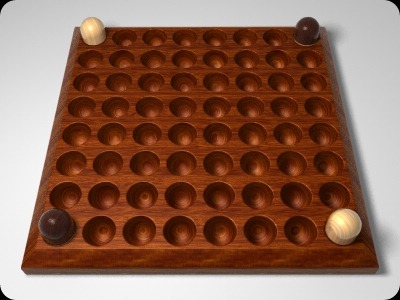

The game begins as shown, with each player starting with two pieces in opposite corners of the board.

The rules are pretty simple. Players take turns either moving one of their existing pieces or dropping a new piece on the board. However, every time you do this, the piece you moved or dropped converts all of enemy pieces surrounding it to its color. Once the board is full, whoever has more pieces on the board is the winner.

If you choose to drop a piece, you must do so in an empty space diathogonally adjacent to one of your current pieces. Once done, you capture all of the surrounding enemy pieces (again, diagonally or orthogonally) to your new piece. Note that captures do not cause chain reactions or anything -- only the pieces immediately adjacent to your piece are captured.

This is usually presented not as “dropping,” but as “cloning” one of your existing pieces into an adjacent square. As the game was originally conceived, the pieces were bacteria that split and infected surrounding areas -- hence the original name, Infection. It’s functionally equivalent to dropping, though, which I believe is simpler to explain. Whatever works for you.

Alternately, you can choose to move one of your pieces. This doesn’t give you the advantage of a brand new piece, but it can often be more useful. When moving, you must move exactly two squares away from yourself, orthogonally or diagonally, in any combination of directions. So you could move to up and then diagonally up and to to the right, or two spaces to the left, etc.

You can’t move into a space adjacent to your current space, but there’s no reason to. If you want a piece there you must drop it there -- which is almost invariably better for you than moving an existing piece.

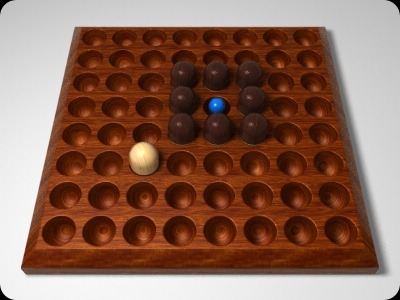

After moving, all enemy pieces adjacent to your new location are captured and converted to your color. When moving, players can “jump” over both their own and their opponent’s pieces. So, for example, given the following board, the white player could jump to the center of the black pieces and capture all of them.

If you can move, you must. If you can’t, your turn is skipped (it’s possible that you’ll be able to move again in a later turn). The game goes on until the board is completely full with tokens, and at the end whoever has the most wins. If a player runs out of tokens, they automatically lose. Ties are possible, and simply counted as ties.

Victory for white; 38 : 26