This game is usually just called Y, but writing that by itself can be a little confusing to people who don’t know what I’m talking about it. Thus I have chosen to use its longer name as the title for this post, and I may refer to as such in other places, but herein it will be known only as Y.

The game is very similar to Hex. Charles Titus and Craig Schensted designed it in 1953, just a few years after Hex became well-known, making it one of the earliest connection games. (Although Titus and Schensted generally get credit, it was independently designed around the same time by Claude Shannon and David Gale, although who exactly thought of it first is a little fuzzy). It’s not a Hex variant per se (you could say the opposite), but it is a connection game, and shares much of the same strategy.

Y is one of a very small handful of games that can compete with my affection for Hex. I believe that this is an incredibly beautiful game with truly interesting strategy and gameplay. More than that I will not say -- read the rules and judge for yourself.

Equipment

There are two boards used to play Y. One of them is a triangular hex grid. The other is the mutant bastard child of a triangular hex grid and a pentagon, producing a board where some of the spaces that should be hexes are actually pentagons, corrupting the strategy and ruining the beautiful simplicity of this game.

I do not like this.

Okay; I’m being harsh. The whole pentagon thing isn’t really a big deal (only three spaces are pentagonal), and it actually makes for a pretty cool looking board. However, it just doesn’t sit well with me. It’s...impure. An interesting idea for a variation, perhaps, but it certainly should not be considered the “official” game (the only commercially produced Y sets are of this flawed variety). But it’s not the worst thing in the world. It’s an interesting idea for limiting the power of the center, but nothing more. The game in its more pure form is superior, and I hereby publicly condone its usage above other boards.

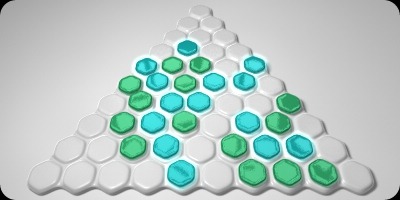

The regular board. I will not even show you the not regular one.

The regular board. I will not even show you the not regular one.Anyway, I’ll only be providing a regular board for you to print. Hook yourself up here. There’s no “standard” size Y board, so I’m semi-randomly picking a size 10 because it fits on the page relatively well and provides a decent, if slightly short, game. It also has a perfect center (this is not the case for all sizes). In my opinion it’s too small to really enjoy the game to its fullest, but it’ll work as you get the hang of the game.

In addition to the board, you’ll need a set of tokens of two different colors. These can be anything, of course, and for a size 10 board you should need around 20-30 per player.

Rules

This will be one of the shortest descriptions I will ever write, simply because the rules to Y are so simple and pure. The play is the same as in Hex: players take turns placing tokens of their own color on any empty space on the board. The first player to form a connection with their stones between all three sides of the board wins (corners count as connected to both sides).

A standard connection

A standard connectionAnd that’s it. The Pie Rule is used to remove the first player’s advantage (immediately after the first stone is placed, the second player can choose to replace it with one of his own stones instead of taking a normal turn; see Hex for a more thorough description). Like Hex, Y can never end in a draw.

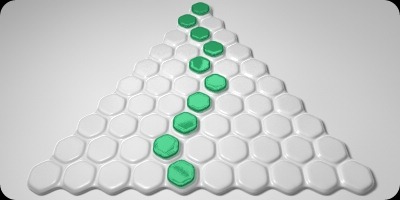

There is one more thing unrelated to the play of the game that you might want to know (it’s interesting!): Y is a generalization of Hex. That is, Hex is a specific case of Y. What does this mean? Well, consider the following Y game:

This is now identical to a game of Hex. Make sense? Of course this situation would never really arise, but this fact is sometimes used to argue that Y is “superior” to Hex because it contains it. You can decide that one for yourself -- get out there and play it!

A connection using a corner

A connection using a corner