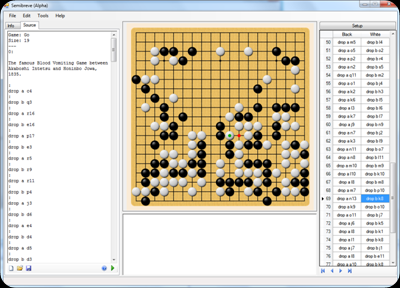

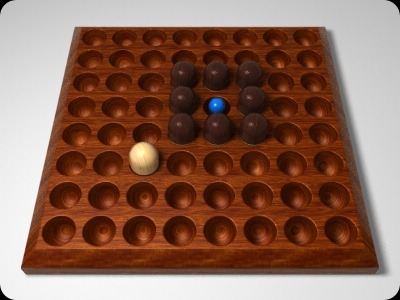

Ladies and gentleman, it’s been a long time coming, but I give you -- Go! In my opinion, this is one of the most interesting games of all time. Everything about it just screams awesome -- the beautiful board, the historical roots, the intensity of the strategy -- it is a marvel both to play and to behold.

Go is the oldest single game that is still widely played today, and has remained virtually unchanged since its conception over 2,500 years ago. Of all the other games of comparable age, Go is the only purely strategic one of which we have any record. Not only that, but it is perhaps the most strategically sophisticated game every created. Seriously. Go strategy has been developing for thousands of years, and no game can even begin approximate its depth. You thought Chess was all high and mighty? It’s got nothing on Go.

And for all this, the rules are some of the absolute simplest in gaming. It can be learned in minutes, but mastered in...never. You cannot master this game. It just can’t be done. Many have tried; none have succeeded. Not even computers can do it. The strongest computer Go programs in the world do not begin to present a challenge to even average players (this is true of many games, but it is especially noteworthy for Go, since it is one of the most popular board games in the world).

The game is properly known as Weiqi in China (whence it originated), Igo in Japan, Baduk in Korean, and by many other names across the world, but Go is the one that reached the West (as a corruption of the Japanese). If you are prepared to tackle the strategic behemoth that is this game, I wish you luck on your quest. It will be a journey to remember.

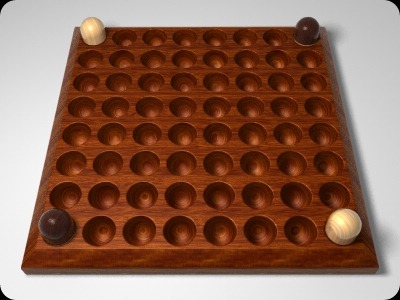

(Note: I made the above image a long, long time ago -- don’t think I’m getting lazy and using someone else’s art or anything. It shows a full-size Go board as well as the traditional bowls, so I thought it would be fitting to include (plus it saved me some much-needed time). The images from here on out will be of a different board I recently modeled and will feature no random columns -- sorry.)

Equipment

The game is traditionally played on the intersections of an 18 x 18 square grid board, which is referred to as a 19 x 19 board (because there is one more intersection than square, of course). A few intersections of the board are marked to help players orient themselves, but these are not vital or probably even that useful for beginners.

Although the standard board is 19 x 19, it is typical for beginners to play on a 9 x 9 or 13 x 13 board to learn the rules (any size board is possible). If you want, you can play on the intersections of a chessboard as a makeshift 9 x 9, or print out a proper Go board here.

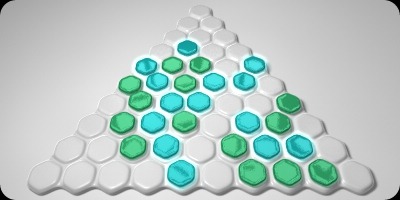

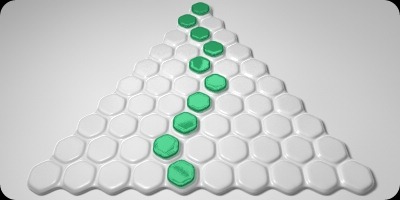

Note that in these illustrations, I’m using an 11 x 11 board for two reasons: it’s small enough that it’s easily visible at such a low resolution, and Go stones look comically large on 9 x 9 boards (they still look pretty big here, in my opinion). As far as I know, no one ever actually plays on an 11 x 11, but that will not deter me.

An 11 x 11 Go board, also known as a Goban

An 11 x 11 Go board, also known as a Goban

In addition to the board, each player needs tokens -- lots of them. For a 9 x 9, about twenty-thirty per player should work, but larger boards will require many more. You can use coins or beads or beans or whatever if you don’t have any Go stones lying around the house. Then, if you decide you’re really into it, you can drop $4000+ on pieces made of semi-precious stones. Not even kidding. Man, I wish I had that kind of money to spend on board games.

Rules

At its heart, the game is very simple. The board begins empty, and players alternate placing stones on intersections of the board. When a stone or a group of stones is completely surrounded by enemy pieces, it is captured and removed from the board. Players may choose to pass their turn if they wish, and when both players pass one after another the game is over.

Okay, that’s it! Get playing.

Actually, that’s close to true. But while the above rules account for about 99% of the game, there are a few more little things here and there that deserve clearing up. And, you may have noticed, there is no mention of either a goal or a victory condition. Who wins? We’ll get to that, but first: some clarification of the above.

Dropping and Capturing

Players take turns placing stones, one at a time, on empty intersections of the board. The goal is to gain “territory” -- basically, to capture areas of the board by surrounding them with your pieces. Like most games that aren’t Chess, black goes first.

(This is important to remember, as there are special rules that apply to the players when it comes time to determine the winner. For the sake of brevity, instead of saying “the person who goes first,” I’ll just say “black,” and expect you to understand what I mean. Or maybe not. We’ll see when I get there, I guess.)

When a stone or a group of stones is completely surrounded by enemy stones, it is captured and removed from the board. Surrounding refers only to orthogonally adjacent pieces -- diagonals have no meaning in Go (hence playing on intersections: pieces are adjacent to the pieces that they are connected to via the lines of the board).

Examples of various captures. In each case, the white pieces would be

Examples of various captures. In each case, the white pieces would be

captured and removed from the game. Note that pieces can be

captured against walls and in corners as shown.

Suicide

There are two restrictions on placement, neither of which is very complicated. The first is stated as follows: you cannot place a piece in such a way that it would cause the capture of your own pieces -- no “suicide” plays, in other words.

Why would you ever do this? Well, if you place a piece in such a way that it and only it would be captured, such as in the corner when surrounded by your opponent’s pieces, the board doesn’t change at all. It’s as if you passed your turn. But you didn’t pass, and thus, even if your opponent passes, the game doesn’t end -- and you can keep doing this forever if you’d like. Suicide plays like this are just unsporting. To the best of my knowledge, it is literally never advantageous for you to kill your own pieces, so don’t worry about it too much. This is not always used as an official rule, since no serious player would ever make a suicide play anyway.

However, take note: capturing of enemy pieces takes precedence over capturing of your own pieces (suicide). So it is possible to play in the middle of a group of enemy pieces, providing that doing so results in the capture of those pieces. Basically you capture the enemy piece “before” it gets a chance to capture you.

If white played in the center of the black stones, he would be completely safe, and the black stones would be captured. If black played there,

If white played in the center of the black stones, he would be completely safe, and the black stones would be captured. If black played there,

however, that would be a suicide play.

Ko

The second restriction is called the “Ko” rule, which you might hear described as “You cannot make a play that would create a position that has previously occurred in the game.” What? That sounds vague and ridiculous -- are you supposed to keep track of every position that has ever occurred in the game? Of course not. As a formal definition it works, I suppose, but it overcomplicates an otherwise very simple rule.

Basically what it means is that the same two pieces can’t be infinitely recaptured. Consider the following board:

Positions where the Ko rule could apply

Positions where the Ko rule could apply

I’ll only discuss the center setup, since it’s the most classic example of Ko. The others will trivially follow. Basically, if white plays in that empty spot, the black stone to the left will be captured. But if black then plays on the new vacant spot -- the spot where his stone was just captured -- he will capture white’s stone and the game will return to the exact same position as before. This could go on forever -- if it weren’t for the Ko rule.

Basically, black just isn’t allowed to do that. It’s as simple as that. White can capture the stone just fine, but black cannot recapture right away: this only applies on the turn immediately following the capture. If black goes somewhere else and white goes somewhere else, then black can recapture the stone on his next turn. (This isn’t a “repeat of a previous position” because of the two new stones.) Now the situation is reversed, and white cannot immediately recapture, and the game continues.

I recently heard what I think is the simplest, most logical, and essentially best explanation of Ko I’ve ever encountered, so I’ve decided to share it here in this update. It is merely that “you can’t make the same move twice in a row” (where “move” includes the capture -- you can play in the same spot as long as you’re capturing a different number of stones, although in reality this almost never happens). I feel rather foolish having spent the past two paragraphs explaining it when that simple statement does a better job, but there you go.

(I originally read it on Cameron Browne’s site, although I’m not sure if he thought of it or not. Either way that site is worth a look around -- he’s a very creative and prolific designer who has done some wonderful things for both 3D and connection games)

Passing

At any point, a player can choose to pass his turn instead of dropping a stone. If both players pass in succession, the game ends. Why would you pass? Well, there will eventually be a point where you just can’t capture any more pieces, and playing more stones won’t do you any good (and by some scoring systems can actually hurt you).

In most “real” matches, players don’t bother playing out to the end of a game. Once the game nears completion, it becomes pretty clear which pieces are going to be captured and which are going to survive, so the players just remove the “dead” stones from the board. This might seem a little complicated to you at first, so don’t worry about it. You can go ahead and play the game out to the finish (i.e., when both of you are out of good moves).

Scoring

Congratulations! You have just learned one of the most elegant, ancient, sophisticated games of all time (I’m kind of a fan). You’ve played your first game -- but who won? Well, that depends on who you ask.

There are many different scoring systems and many more specific ways to count up points, but I will be explaining the most simple and, in my opinion, most logical one here. The different scoring systems really aren’t that different in terms of the outcome of the game, and usually only differ by about a point -- not a big deal (for full-size games, scores end up around 180. One point rarely makes a difference).

So here you go: first, count up all of your stones. Easy enough. Then count up all of your territory. Now, territory is really very intuitive, although it’s a little hard to explain verbally. It is essentially all the spaces that are surrounded completely by your own stones. More accurately it is any space that cannot be connected, through other empty points, to one of your opponent’s stones. Any space that can be connected to both your and your opponent’s stones is called dame and belongs to neither of you -- this will very rarely occur if you play the game out fully, so you probably don’t need to worry about it for a while.

Usually, if there is a tie, white wins the game, because he had the disadvantage of going second (more on that below). This is not technically an official rule, but it’s usually used, and I recommend you play as such.

So take, for example, an incredibly simple endgame:

A very imaginary endgame. Just go with it.

A very imaginary endgame. Just go with it.

A game would never end like this, but it works as an example just so you can see how scoring works. It’s pretty clear to see each player’s territory -- black controls all the spaces to the right and white controls all the spaces to the left. So who wins? If I counted correctly, black has 15 stones and 45 spaces of territory versus white’s 15 stones and 46 spaces of territory. White wins by a single point.

A more realistic endgame might look like this:

Black has 50 stones and 19 spaces; white has 36 stones

Black has 50 stones and 19 spaces; white has 36 stones

and 16 spaces, making black the clear winner

This type of scoring is known as “area scoring” and is the method used in China. “Territory scoring,” the Japanese method, is a bit more complex and requires you to keep track of how many stones you capture throughout the game. Don’t worry too much about that, though. Area scoring will do you just fine.

And there you have it. Almost. One last thing:

Komi

As is the unfortunate case with most games, the person who plays first has a noticeable advantage. And, like most placement games, it’s a pretty significant one with Go. To compensate for this, white is usually given a bonus number of points at the end of the game. The actual number of bonus points has varied over the years, but the currently accepted number is 7 bonus points to white for a 19 x 19 board. Since you’ll probably be playing on a 9 x 9 when you start out, though, this doesn’t really help you much.

There is no regulation Komi for such a small board. It is much debated what it “should” be, and there is an interesting dilemma: since the board is so small, fewer points are scored (around 40 per player vs. 180 per player on a full-size board), thus 7 points make a bigger difference. However, since the board is so small, black has a much greater advantage. So, what to do? I’ve heard 4-6 suggested as Komi for such a small game. The jury is still out on it, though. You’ll have to decide for yourself. (I suggest 5.)

In reality, the usual Komi is 7.5, not 7. Why on earth is this? Well, it’s simply a more complicated way of saying “when there’s a tie, white wins.” Since there’s no way black can score half a point, the game will never technically be a tie -- that half point will push white over the edge.

Note that the Komi must be agreed upon by both players before the game starts -- no bickering after the fact.

Other Fair Systems

If you really don’t like Komi but still want to reduce black’s advantage, try this: play two rounds, switching off colors. It is assumed that black will win both rounds. If this is the case, whoever wins by a greater margin is the winner of the match (tied games go to white by a margin of .5 points). Same if white wins both rounds (unlikely, but possible). If white wins one and black the other, then the player who won with white is the victor. Note that this is my own personal system and might have a crippling flaw of which I am unaware, but I think it works pretty well. Ties are possible, if both players win with the same colors by the same margin.

Or, if you don’t want to play multiple rounds, you can use the Pie Rule instead. This isn’t frequently used with Go, although it could theoretically work...maybe. Basically one person plays the first black stone, and the other person decides who will play as black and who will play as white. Thus the first person will place the stone in a position that isn’t too good or too bad, since he may or may not play with it. Unfortunately, the nature of Go is such that this really doesn’t work very well. No matter how bad a position you play for your first move, it’s almost always better than going second, so your opponent would pretty much always swap (maybe he doesn’t know that, though?). For a more thorough discussion of the Pie Rule, check out its description on the Hex page.

Another way is a weird combination of the Pie Rule and Komi, that’s a compromise I particularly like: one person chooses the Komi, and the other person then chooses who will play which side. So if the Komi is too low, the second person will play as black, whereas he might pick white if the Komi is tempting enough. This sort of skirts around the issue of “What is the best Komi?” by leaving it up to players to decide in a fair and balanced way. You’ll have to have some experience with the game, though, to know what a “good” Komi is (try 4-6 for a 9 x 9).

Terms

These are a few key terms (there are tons of weird Go words I’m not including) that you don’t have to know to play the game, but that you might find interesting from a purely academic standpoint. Is that just me? Damn.

Liberties: these are the official names for the empty spaces adjacent to a stone or a group of stones. When a group has no more liberties (i.e., is surrounded) it is captured.

Atari: when a stone or group has only one liberty, it is “in atari.” This basically means that it’s in danger of being captured on the next turn.

Eyes: single holes in groups of stones are called eyes. More formally, these are “internal liberties.” They’re important.

Life and Death: ...and here’s why. When a group of stones has no eyes or only has one eye, and cannot be developed any further, it is “dead,” and its capture is inevitable. If a group has two or more eyes, however, it is “alive” and cannot be captured no matter what (since playing in one of the eyes would be a suicide move for your opponent).

Handicap: when two players of highly disparate abilities face each other, it is customary to provide the weaker of the two players with an advantage. First of all, the weaker of the two will play black, and white will receive a Komi of only half a point (read: white wins in the event of a draw). In addition, black may start with a number of stones already on the board, positioned at the marked points. The number depends on the difference in skill (usually based on formal rankings). It’s a very interesting system that allows beginners to play against more skilled players without getting utterly destroyed (Chess could use something like this, in my opinion).

Black’s victory condition

Black’s victory condition A few turns into the contract phase

A few turns into the contract phase A game won by white

A game won by white

Game Setup

Game Setup Examples of various moves. I didn’t include any examples of switching.

Examples of various moves. I didn’t include any examples of switching.  Victory for white

Victory for white

Game setup

Game setup Possible drops in green; possible moves in blue

Possible drops in green; possible moves in blue Owned. Note that this is the largest capture possible in the game.

Owned. Note that this is the largest capture possible in the game. Victory for white; 38 : 26

Victory for white; 38 : 26

An 11 x 11 Go board, also known as a Goban

An 11 x 11 Go board, also known as a Goban Examples of various captures. In each case, the white pieces would be

Examples of various captures. In each case, the white pieces would be  If white played in the center of the black stones, he would be completely safe, and the black stones would be captured. If black played there,

If white played in the center of the black stones, he would be completely safe, and the black stones would be captured. If black played there,  Positions where the Ko rule could apply

Positions where the Ko rule could apply A very imaginary endgame. Just go with it.

A very imaginary endgame. Just go with it. Black has 50 stones and 19 spaces; white has 36 stones

Black has 50 stones and 19 spaces; white has 36 stones

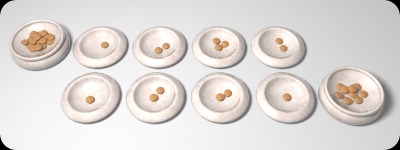

Setup

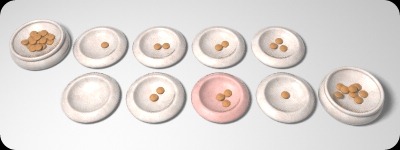

Setup For example, if your opponent had one bean in his second cup

For example, if your opponent had one bean in his second cup If you had four beans in your first cup and sowed them, you would get this.

If you had four beans in your first cup and sowed them, you would get this. A blocked cup

A blocked cup An example endgame. That isn’t even real.

An example endgame. That isn’t even real.